What is Patina?

“Patina” is a culinary term for the acquired change in the appearance of the surface of a cooking vessel.

With a Professional Steel pan, a patina develops when fat comes into contact with the surface of the metal.

The fat penetrates the material and by doing so, it transforms from a dull and dry surface into a slick and supple one.

Why is Patina better?

There are numerous benefits of the Patina non-stick surface on a Carbon Steel pan, especially when compared to a general PTFE non-stick coating. The main advantage is its durability;even if it is removed through over-heating, scratching or an inappropriate washing method the surface can be renewed and the pan can be used with a non-stick release again. In contrast, a chemical non-stick coating, such as PTFE, is prepared and sprayed on the pan by the factory. Once this manufactured coating starts to peel off, crack or just loses its non-stick release then it has become obsolete for further use.

Thus, the durability of a Patina non-stick surface is clearly superior to a general non-stick coating. But why are non-stick coatings still so much more popular all over the world? There are a few reasons for this but the main reason is the difficulty of actually getting a cold rolled grey carbon steel pan (the material of Professional Steel and which as well as cast iron, is most suitable for the development of the Patina), to be seasoned and re-seasoned with a Patina non-stick surface. The advantage of a hot rolled Professional Black Steel is that the pan is already pre-seasoned so the consumer can start using it immediately, without the need to bond oil (season) to the pan before use. However, even with black steel pans, the surface will still need to be re-seasoned at some point, so the same difficulties with seasoning still exist, like they do with cold-rolled grey steel and cast iron.

Why is it difficult to season a steel pan?

Despite the fact that carbon steel, and even more so cast iron, have been used for a long time as a material for cookware there is still no agreed upon consensus among experts in the industry for what is the best method to bond oil (season) to these type of materials. Even to this very day, despite much discussion on the internet, there is no agreement about which is the best oil to use; for how long the oil should be heated on the pan; how many times the oil should be heated on the pan; or even which is the optimum temperature to heat the oil at in the oven.

However, before we outline what these differences are and why they exist, it is important to note there are some points of agreement for getting the best possible patina (seasoning) on a steel pan. These are:

- The oil should be an unsaturated fat.

- The oil that is polymerized on the pan should be a very thin layer.

Unsaturated fats for seasoning

On a molecular level, all fats are composed of triglycerides—a compound of a molecule of glycerol bound by three fatty acids. A glycerol is a short 3-carbon chain that acts as a common frame to which three fatty acids can attach themselves, and with a couple of oxygen molecules tacked onto the end. Each of these carbon molecules has the ability to link to up to two hydrogen atoms.

There are 3 types of fatty acids:

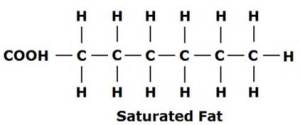

1. Saturated: The carbon chain is saturated – filled to capacity – with hydrogen atoms: there are no double bonds between carbon atoms, so each carbon within the chain is bonded to two hydrogen atoms.

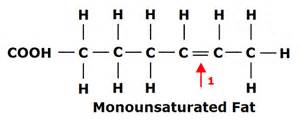

2. Monounsaturated: Two adjacent carbon atoms are missing a hydrogen atom and instead form a double bond with each other.

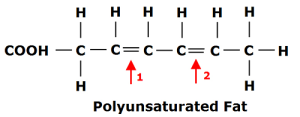

3. Polyunsaturated: Two or more sets of carbon atoms form double bonds with each other.

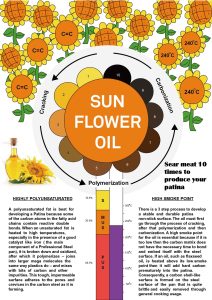

So either a monounsaturated or a polyunsaturated fat is best for seasoning because some of the carbon atoms in the fatty acid chains contain reactive double bonds. When an unsaturated fat is heated to high temperatures, especially in the presence of a good catalyst like iron (the main component of a Profssional Steel pan), it is broken down and oxidized, after which it polymerizes – joins into larger mega molecules the same way plastics do – and mixes with bits of carbon and other impurities. This tough, impermeable surface adheres to the pores and crevices in the carbon steel as it is forming.

Thin coats of oil

The reason a patina surface is non-stick is because it is hydrophobic – it hates water. A well-seasoned Professional Steel pan will have a slick and glassy coating. This is best achieved by heating multiple ‘very’ thin coats of oil on the surface of the steel. A thin layer produces the best results because the patina is a three-step process: cracking; polymerization; and then carbon deposition. If too much oil is spread on a Professional Steel pan polymerization can be achieved but there will not be sufficient carbon deposition.

So to recap, we know that to achieve the best possible non-stick patina we need to use an oil which has a high unsaturated fat content, and it needs to be applied in very thin layers. If not, then the oil is less likely to polymerize properly, to form a tough, durable coating, and later carbonize, so it bonds to the steel surface securely for a longer lasting coating surface.

However, this is where agreement or any kind of consensus, among those who have experience in seasoning either a carbon steel or cast iron pan ends. First of all, one particular bone of contention, even to this day, is: what is the best cooking oil to create a patina non-stick surface?

Which oil should be used for seasoning?

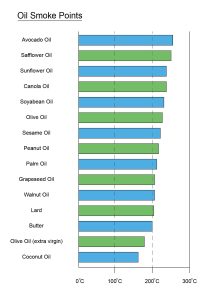

When cooking with oil it is essential that the oil never surpasses its smoke (flash) point. This is because once oil is heated above its smoke point it then starts to degrade, and release something called free radicals which are carcinogenic to the human body. So for example, when stir frying, oil with a high smoke point, such as safflower oil, needs to be used because for this type of cooking the pan will need to reach a high temperature. However, for other types of cooking, such as frying an egg or sautéing some potatoes, then oil with a lower smoke can be used. This is also generally advisable because oil with a lower smoke normally has more flavor. So for cooking where you would like to infuse the ingredients with some extra flavor, then this would be another reason to use oil with a lower smoke point.

In stark contrast to cooking however, when seasoning a carbon steel pan, it is in fact essential that the oil gets heated above its smoke point. If it does not then the oil will not polymerize fully and then later carbonize, to form a stable and durable patina non-stick surface. This is essential to both protect the pan from oxidation and to form a non-stick surface for cooking.

As noted earlier, there is no agreed upon consensus regarding which is the best oil to use to create the patina non-stick surface. On most websites the general advice is to use is vegetable oil. Others have said that that avocado oil, because of its high smoke point is the best for seasoning; while some people have other suggested spray-on canola oil with additives gets the best results.

This debate was developed further when in 2010 a blogger, named Sheryl Canter from the USA, argued in what would become a widely circulated post, that flaxseed oil, the food grade equivalent of linseed oil (a drying oil), should be used to season either a cast iron or carbon steel pan. She argued that because flaxseed oil has a high content of Omega-3 fatty acids, that over a prolonged exposure to high heat, these fatty acids, once they pass the smoke point of the flaxseed oil, combine and cross link together to form a strong, solid matrix that polymerizes to the pan’s surface. Her thesis was given further credence when Cook’s Illustrated, the well-respected cooking journal that even has its own very science cooking department, gave this new seasoning method a very positive review. In it they wrote

“We carried out Canter’s approach on new, unseasoned cast-iron skillets and compared them with pans treated with vegetable oil – and the results amazed us. The flaxseed oil so effectively bonded to the skillets, forming a sheer, stick-resistant veneer, that even a run through our commercial dishwasher with a skirt of degreaser left them totally unscathed”.

So, is a drying oil such as flaxseed oil the best oil to use to develop a patina non-stick surface?

A drying oil, such as linseed oil, does undoubtedly produce a hard, polished finish, similar in nature to a those used by artists once they have finished a painting. Flaxseed oil, which is the food grade equivalent of linseed oil, does boast six times the amount of omega-3 fatty acids as vegetable oil. Within flaxseed oil is Linoleic acid, which is a carboxylic acid with an 18-carbon chain and two double carbon bonds. So at first glance, with its high number of carbon atoms, which are more readily available to be broken down and deposited on to the steel’s surface than a more saturated oil such as vegetable oil, flax seed oil does appear like a highly suitable oil to season a pan with.

A drying oil, such as linseed oil, does undoubtedly produce a hard, polished finish, similar in nature to a those used by artists once they have finished a painting. Flaxseed oil, which is the food grade equivalent of linseed oil, does boast six times the amount of omega-3 fatty acids as vegetable oil. Within flaxseed oil is Linoleic acid, which is a carboxylic acid with an 18-carbon chain and two double carbon bonds. So at first glance, with its high number of carbon atoms, which are more readily available to be broken down and deposited on to the steel’s surface than a more saturated oil such as vegetable oil, flax seed oil does appear like a highly suitable oil to season a pan with.

However, there are others with experience in seasoning a pan who have strongly disagreed that flaxseed oil is the best oil for producing a soild, durable patina a pan. First, they contend that the explanation by Sheryl Canter, and later supported by Cook’s Illustrated, that the reason why flaxseed oil creates a patina non-stick surface is actually incorrect. The seasoning process is not initiated with the release of free radicals, which then cross-link to create a hard surface. As was noted earlier, seasoning in fact begins with the oil cracking, then polymerization, and last it proceeds to carbonization. Once the polymerization process is complete then the free radicals are actually driven off and combine with nitrogen or oxygen in the air to form smog.

The second point of contention that flaxseed oil, because of its numerous double carbon bond configuration, produces a harder patina non-stick surface is also incorrect. In fact, all oils when heated over a period of time will form a hard polymerized surface eventually; the difference with flaxseed oil is that it will form a hard surface faster. In terms of saving time and added convenience a Patina which can form faster might seem advantageous, but in fact, the faster hardening process of a drying oil, such as flaxseed oil, is actually detrimental to producing a highly durable patina non-stick surface. This is because it does not give the necessary time for the carbon matrix to bond and embed itself with the steel surface. The effect of Flaxseed’s low smoke point is to add hard carbon prematurely into the seasoning, meaning the oil does not polymerize fully. So by creating the Patina too quickly, a carbon shell-like surface is formed on the steel surface of the pan. This might look quite hard, but it is in fact quite brittle, and the Patina will not be that durable to withstand general cooking usage.

So, if not Flaxseed, then what?

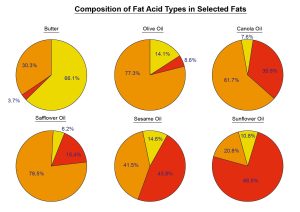

In conclusion, for optimum seasoning on a Professional Steel pan, the oil needs to have both a high polyunsaturated content and a high smoke point. A high smoke point is useful to allow the oil time to polymerize and then carbonize fully, but if that oil is also highly polyunsaturated then there are more readily available reactive carbon atoms to deposit on the steel surface and create a durable patina surface. A patina which has a dark, black sheen, is one with a higher carbon content and one that is more likely to be more durable for use when cooking.

Therefore, with these properties in mind, Professional Steel recommends Sunflower oil for use when cooking. It has both a high smoke point and it is also highly polyunsatuarated. If you cannot find Sunflower oil, then Soyabean oil is another good alternative to develop the Patina non-stick surface.

Reference

Websites

http://www.kentchemistry.com/links/organic/cracking.htm

http://www.genuineideas.com/ArticlesIndex/castironseasoning.html

http://www.scienceofcooking.com/why_food_sticks.htm

http://www.scienceofcooking.com/cast_iron_cooking.htm

http://www.seriouseats.com/2014/05/cooking-fats-101-saturated-unsaturated-trans-fats-guide-faq.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seasoning_(cookware)

www.cookingissues.com/2010/02/16/heavy-metal-the-science-of-cast-iron-cooking/

http://sherylcanter.com/wordpress/2010/01/a-science-based-technique-for-seasoning-cast-iron/

https://www.cooksillustrated.com/how_tos/5820-the-ultimate-way-to-season-cast-iron

http://www.goodeatsfanpage.com/collectedinfo/oilsmokepoints.htm

http://www.chemicalforums.com/index.php?topic=39242.0

http://firesciencereviews.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/2193-0414-1-3

Books

H. Blumenthal/ T. Lister: Kitchen Chemistry

H. McGee: On Food & Cooking, The Science and Lore of the Kitchen